As anyone approaching their twenties ravaged by hormones and victim of outbursts of devastating infatuations, I did some crazy things. Acting foolish just to fit in, neglecting family reunions to feel like a rebel, weekly looking for the right clothes to show off my new personality with. The usual. I don’t regret being that kid, but one thing I do regret is doing something the full extent of which would hit me much later in my life.

One day, absolute certain of my feelings, I grabbed a photograph of me around the age of five and gave it to the girl that I thought I was going to spend the rest of my life with. The picture was a matter of playful anecdotes in my house, displaying me with a nice red hat, colourful shirt and fancy shorts playing the drums left unattended at a town festival. My parents and my grandparents had always remembered that day as clearly as I’ve never been able to. Nobody noticed the absence of the photograph for a long while. Some years later, my grandmother was arranging old pictures to display in her living room and asked me for the drums one. I stood silent first, then I invented random words about not being sure where my mum could have put it, and left the room to hide somewhere. I cried, as I am practically doing right now while I relive this episode in my head.

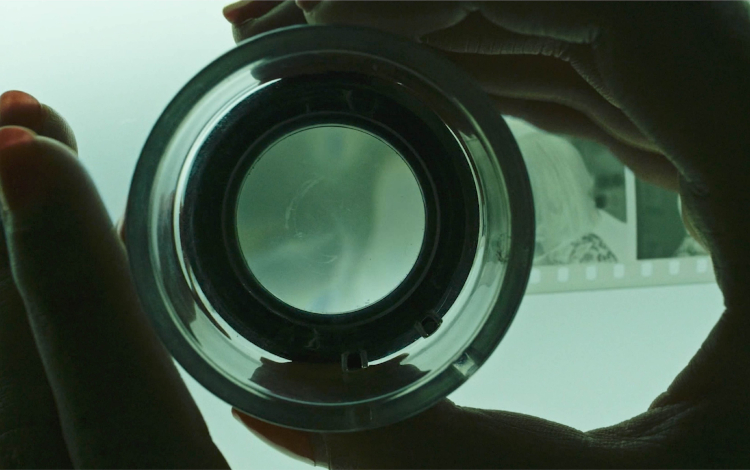

I am thrown back to that photograph and to what it meant to my grandmother by Sophy Romvari’s latest short film Still Processing. The film starts with a box of previously unseen family photos and videotapes which brings Romvari to confront herself with memories that were waiting to be awakened. A fairly simple premise, probably something that can happen to anybody, but Romvari does not limit herself to filming how photographs inform the recollection of our family’s past.

Still Processing is how the Canadian director reacts at being reminded of the trauma of losing two of her brothers. Understanding the pictures in front of her implies absorbing the loss through the process of film-making. In making sense of the images and filming how she does it, Romvari makes her, her family, and everyone else willing to be there with her short film, a part of a process that is bound to be perpetual. We can learn to live with a loss of a dear one and go on with our lives, but can we really let it go? Someone or something could trigger memories unexpectedly, and how we face those memories is up to us.

Romvari chooses to put her camera in front of the photos and the videotapes, presenting them along with her reaction and that of her brother. The past is alive again, the present never really free from it. It’s as if for her the images alone were not enough to comprehend the memories. Only by processing them she is finally able to connect with her family, see how it was and what is lost. The fact that the images are as new to us as they are to her places us closer to where she stands. We are not her family, but we are as near as possible to what she feels while working on the objective necessity of the past.

At some point in Still Processing Romvari says that trauma is relative, which is true if we consider the specificity of it. After all, I have never experienced something along the lines of what she has been through. However, Still Processing shows that trauma stops being relative whenever we are able to share how it affects us. Romvari opens the wounds for us to see with a grace that refuses commiseration and asks for empathy.