A work of art is ever-changing. It never ceases to approach you in unexpected ways and, even when you know what is coming, a work of art knows that it can surprise your mental agility in an instant. It’s as living as the artist, and just as the artist explores different directions, a work of art moves and challenges you constantly. If it doesn’t move or it stops fighting, then there is little art involved in it.

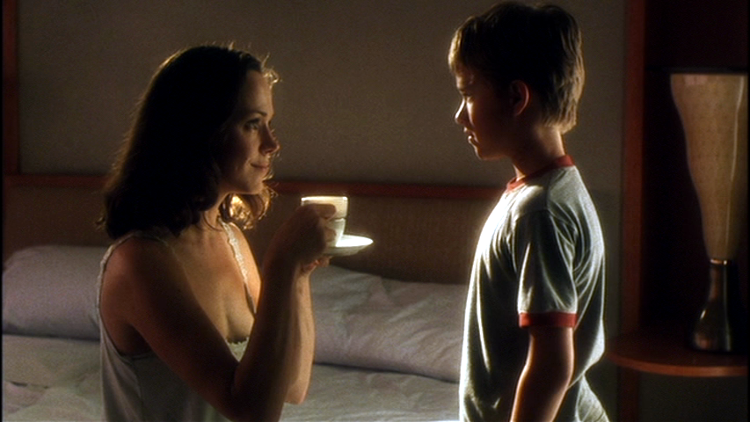

A recent review of A.I. Artificial Intelligence by Alec Lane prompted me to reacquaint with a fundamental piece of my love for cinema. Lane’s write-up is not only the best commentary on A.I. I’ve ever read,1 it also makes a convincing and beautifully thought point: there is more Steven Spielberg than Stanley Kubrick at play here, and only Spielberg could have taken the film to its incredible heights.

This is such a fascinating take for me, because I’ve always thought of A.I. as a film from two minds. I superficially attributed the first and third act to Kubrick, and the second, longish one to Spielberg. My error was the consequence of the limited knowledge of Spielberg’s career I had until recent years. I deemed him a somewhat too dully popular and happy-ending seeker, so my view on his works had been impeded by such unjustified snobbery.

However, A.I. felt immediately special. After the first viewing, it became a fixation. I devoured the special contents on the two-disc DVD edition, collected articles and books about and at the basis of it, bought the Blu-ray, repeatedly annoyed everyone around me over the years, and wrote about it on one of my long-lost affairs with blogging.2

Why do I feel compelled to revisit A.I. so much? It has to do with its nature. The more I grow old, the more I read and learn. The more I know, the more I find in the film. Surely this is a process applicable to many other films as well, but it’s particularly gratifying with A.I. because there seems to be no end at the angles from which it can be looked at. The fairy tale as an allegory is just the first step. As soon as you start peeling layers away, A.I. offers questions, more than answers, on pathos and ethos, immortality and spirituality, hierarchies and preservation, race and manipulation, science and technocracy, parenthood and childhood, the fallacy of memory and the poignancy of loss, the future and our responsibility towards it. The questions come viewing after viewing, the answers must be looked for elsewhere. The fact that a film can provoke thoughts on life and time, while pushing me to dig further to understand the topics it is covering, makes it instantly invaluable.

A.I. has changed over the years. At first it appeared to me as intelligent entertainment, a smart blockbuster from a popular cinema mastermind often misunderstood. Then it started raising philosophical issues, pointing its fingers at the viewers and the world around them, while long due appreciation for the craftsmanship eventually begun. Finally, it placed itself as a unique piece of science fiction, unparalleled ever since and standing firm as one of Spielberg’s most accomplished works—if not the most accomplished one.

I already explored the unpredictability of judgement,3 but there is more than a shift in opinions here. A.I. poses itself as a demanding work of art. It can never be completely grasped, because we are never an absolute. We face art at different points in time, just as art reflects the times when it comes to life. But it’s only when art grows old and overcomes the days immediately following its creation and reception that we are confronted with something more intimate than an expression of beauty. Art brings us to self-discovery and understanding, positioning itself as the necessary means to make sense of what is to come.