Bohemian Rhapsody reminded me of how difficult it is to tell a story more or less well-known. Questions of accuracy, respect, and fan-service are inevitable, as inevitable is the pressure behind a work that must deal with a popular figure. Bohemian Rhapsody follows the conventional biopic path, unfolding mechanically like a Wikipedia entry. It limits itself to bits and pieces of a subject too complex to be tamed, and it fails miserably at showing us that there is more to Queen than a greatest hits collection.

Nonetheless, biopics have always fascinated me, especially since I am an avid reader of biographies and autobiographies. I enjoyed Control and Love & Mercy, and I loved Bird and I’m Not There. None of these has had the overwhelming power of Ivan the Terrible on me, but that’s because Sergei Eisenstein was not from this planet. Had he heard me calling his unfinished masterpiece a biopic, I am pretty sure he would have slapped me. The last biopic capable of shaking me up in a manner similar to Eisenstein’s was Michael Mann’s Ali. What takes Ali closer to Ivan the Terrible than to the other above-mentioned films is where the focus is.

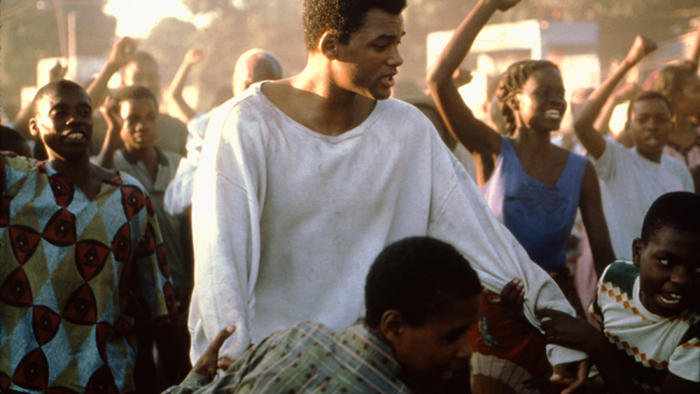

Most of the time, biopics take few liberties. In the worst cases, they tend to resemble documentaries. Too close to the source material, too constrained in their view, they add little to nothing to the formulaic one-man show. It’s a pattern so obvious it has been mocked many times (e.g., Walk Hard). Ali defies this schema right from the start. In ten minutes of brilliant montage, with juxtapositions of music, boxing training, and episodes of the champion’s life, Mann avoids the “once upon a time…” cliché, contextualises his character, and then jumps straight into Ali’s turning point: the glorious fight with Sonny Liston. The fact that the film opens without a single word from Ali, a man as powerful with his voice and words as he was with his fists, feels like Mann immediately stating his position against the biopic genre.

But there is more on this beginning. In a conversation with Bilge Ebiri, Michael Mann singled out Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties by Mike Marqusee as the best book on Ali. Not so surprisingly, the book begins with the same Clay-Liston fight Ali does. I don’t think this is a geeky touch. On the contrary, I feel like Mann connected on more than one level with Marqusee’s pages, and decided to portray a complex figure without losing sight of the significance of the events that surrounded it. And that is why Ali deals with only ten years of Muhammand Ali’s life. With the cultural and historical era at the centre of the picture, we have a deeper sense of the nature of Muhammad Ali’s choices in the most important timespan of his life.

Mann never steps back from the possibilities in front of him. The afro-camera, as it is ironically referred to in the Making Of, is as simple as it is ingenious: placed on the head of the fighter, it puts the viewer in between the punches, augmenting our sense of participation in the drama called boxing. The trick is not to abuse of such a device, and Mann knows when to stop. And the same goes with the political implications: Mann hints, without confirming it nor denying it, at the FBI plot behind Malcolm X murder. It’s enough. It’s up to us, now. If only Freddie Mercury sexuality could have been treated with this cleverness.

This is the kind of personal involvement most biopics lack. Ali could not have been done by someone other than Michael Mann. His vision, his composition, his realism, his hero, his moments of tenderness. It’s all here. Never for a second you feel like these images come from a book, or like there is a documentary that tells it the same way but in a different style.

And then comes Will Smith. I won’t question Rami Malek preparation for the role of Freddie Mercury, although those ridiculous fake teeth still keep me up at night sometimes. I know Freddie Mercury’s voice is unique, but he was a unique persona too. Much like Muhammad Ali, which is why Will Smith’s performance is something Malek’s should have studied closely. True, Smith had the chance to have Muhammad Ali on the set, but instead of arbitrarily hiding sides of his vibrant personality, Smith and Mann bring everything out in subtle ways. His braggadocio, the complete transformation from Cassius Clay into Muhammad Ali, his religious belief, his humour and his charm, his adultery. By the tonal shifts in the voice and the studied movements (the walk, the eyes), all the controversial traits of Ali emerge without compromising the nature of the film. At his best, Malek mimics Mercury’s flamboyant stage presence and mercurial temperament, but he stops there. There is one idea of Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody, and that’s all we get.

While Bohemian Rhapsody adds nothing to a trite custom, Ali redefines the biopic and it offers itself as one of the few, real alternatives to an annoyingly standardised approach to biographical material.