Funny how volatile judgement is. I remember enjoying Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One while reading it, and then time has almost entirely overturned my appreciation for it. I was still dealing with the rise of my negative opinion about Cline’s work the first time I saw Steven Spielberg’s adaptation this year, hence no surprises my bias ruined my enjoyment. Upon watching Ready Player One again last Sunday, a totally different film unfolded on the screen. I refused to oblige the bias, and sat in ecstatic amusement while Spielberg built a world of wonders in front of me.

I instantly connected my feelings of joy to the ones I experienced when Star Wars entered my life as a kid and set my love for cinema ablaze. This is not coincidental, because Ready Player One is the closest Spielberg has ever come to match the visionary of visuals that is George Lucas.

However, I had kind of forgot about George Lucas. When the prequels came out I was one of those fans who felt betrayed and insulted. I went in looking for something the prequels are not: the original trilogy. As a result, nostalgia played the same role my opinion of Cline’s book played with Ready Player One. After Revenge of the Sith, from time to time I revisited the original trilogy for nostalgia sake, but my love for George Lucas was weakening, and even those three films were losing my devotion year after year. Cinema changed, I changed, and by now that galaxy was literally far, far away.

Ready Player One left me with the desire of revisiting George Lucas’ works. I took the experience of the second viewing as a sign. The Star Wars prequels needed another chance. If it happened with Spielberg, it could happen with Lucas as well. It just felt like I owed it to him.

The Phantom Menace surprised me the most. The weakest chapter among the prequels and the one that sparkled my delusion back then, The Phantom Menace lays the grounds for all the politics to come. The pod race is as amazing as I remembered, pure kinetic power at barely controllable speed. The Wachowksis surely memorized this race before devising the absolute madness of Speed Racer. On the other hand, Lucas is not ready to fully embrace the CGI like he wishes, or maybe it’s the CGI not ready for him yet, because The Phantom Menace doesn’t always look as beautiful as some of its best images. The fantasy of its author is impeded by the technological limits of the time.

It’s only with Attack of the Clones that he finally gets what his heart deserves. Lucas has now everything he needs to elaborate an imaginary universe, and he understands what it takes to go beyond the mere creation of spaces for the action to occur. He experiments with colour shifts, crafting backgrounds that intensify the psychological warfare within Anakin. There is no manichean distinction between light and shadow any more, a stylistic choice which reflects the blurred distinction of good and evil typical of Eastern philosophies. The most experimental episode of the saga in terms of formal achievements, Attack of the Clones also starts posing the question further explored in Revenge of the Sith: what does it mean to be a Jedi Knight? Star Wars has never explored so deeply the moral ambiguity of its heroes.

Reinvigorated by the first two chapters, I approached Revenge of the Sith with even more curiosity. Of the three, it’s the only one that the younger me ended up moderately liking, but what would I think now that my perspective on The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones has changed?

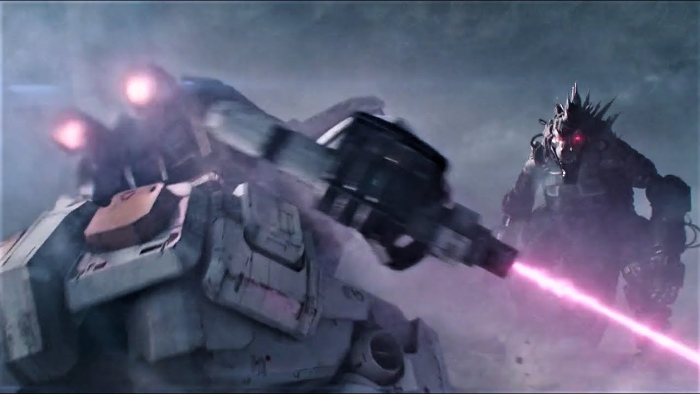

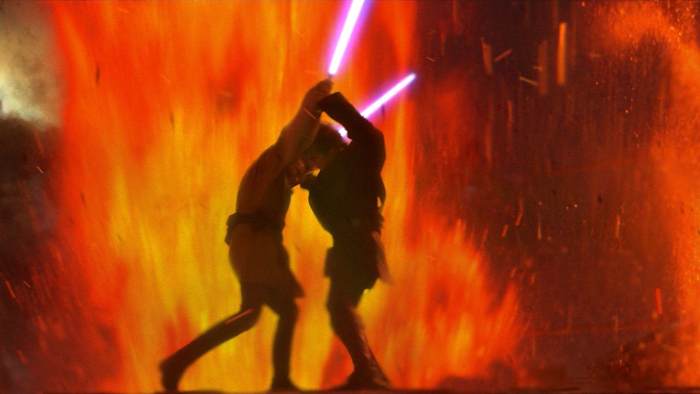

Lucas pulls you right into a furious battle in space. It’s already clear he is now dominating the resources at his disposal. The CGI is slick, and he can now stage impossible acrobatics, invention after invention, like he has always been trying to do. This is the dream come true of a kid possessed by the spectacle of images moving on a screen. Here Lucas is creating the defining epic war for its saga, moments unparalleled in proportion and unique in technique. Amidst the grandeur of the fights, the pivotal drama of Star Wars reaches its peak. Anakin falls prey of the Dark Side, he sacrifices everything for the promise of untamed power.

Moreover, Anakin eventually has to deal with the political dilemma built up so far by The Phantom Menace and Attack of the Clones. He struggles to find hope in democracy because it appears to be no democracy when everyone is above you. He fails to comprehend the implications of a ruling government because he wants immediate answers to his questions and immediate actions to benefit from. All that matters has to be within his reach, everything else is simply marginal. The fear of losing what he has is exploited by Darth Sidious and in the end takes Anakin to the point of no return.

It’s the same fear Darth Sidious works with to obtain the position of leader of the soon to be Empire. Fear is the actual phantom menace. It attacks and wins over the minds of a great Master Jedi such as Yoda. He suspects but can’t act, he waits and can’t see, stopped by a feeling greater than his belief in the Force. His exile is the supreme failure of the Jedi Knights. Revenge of the Sith reveals itself as George Lucas most ambitious masterpiece.

The Star Wars prequels present a past the original trilogy struggles to confront with. The scale of the universe designed by George Lucas here is indeed too much for the possibilities cinema offered in the late seventies and throughout the eighties. When they came out, the prequels had fans lacking the sane distance needed for an appreciation devoid of misconceptions. Now may be the right time to revisit The Phantom Menace, Attack of the Clones, and Revenge of the Sith, and at last understand the mighty vision of George Lucas.