Lately I’ve found myself deeply immersed in Michel Chion’s work on Stanley Kubrick. I took it as a reason to go back to Kubrick’s oeuvre, connecting the dots and trying to figure out what the great director means today.

In particular, I’m thinking about what his works mean for me now. I remember being shocked by A Clockwork Orange at 14. I remember buying 2001: A Space Odyssey on VHS and watching it three times in two days struggling to understand the “what?” and the “why?”. I remember sitting alone with just two other guys in an empty movie theatre waiting for Paths of Glory to begin. I also remember comparing Full Metal Jacket to Saving Private Ryan in a conversation with my grandfather — and I’ll never forget his colourful defence of Spielberg’s effort.

Nonetheless, it’s been a while since my last revisiting of a film by Kubrick. Of course Chion’s book is not just a reminder, but an in-depth analysis of all Kubrick’s works. The French critic doesn’t hide his preferences. On the contrary, he is plain enough to say which films he likes less in the first pages.

I tried not to let Chion’s opinions interfere with my own conclusions. Two films had an unexpected effect on me: 2001: A Space Odyssey and Eyes Wide Shut.

Young and with few clues in film criticism, I was the kind of film geek ready to come to my fists to defend 2001: A Space Odyssey. I praised the camera work, the editing and the use of music as if nobody better than me knew what I was talking about. Today 2001: A Space Odyssey has a different effect on me. The long stretch of visual tricks in the last part left my eyes tired and eager to move on. It felt more like a series of images to contemplate from a distance. As philosophers do, Chion says, but I’m not used to doing that with films.

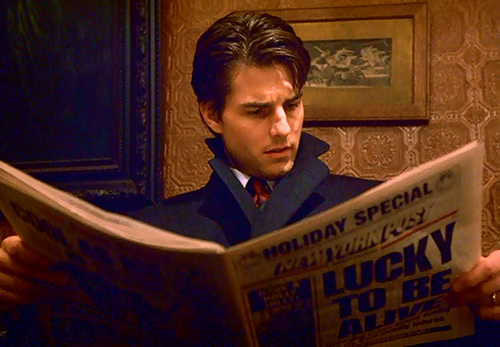

On the other hand, Eyes Wide Shut turned out to be the one I love the most. I read Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle right after watching it and I watched Eyes Wide Shut again once I finished the novella. It’s such an inspired and inspiring film. Its elegant usage of words and sounds is only matched by the careful lightning and editing. There is so much going on in every silence, in every gaze. Kubrick never questions his characters actions, and characters do the same. As Chion notices, the only character who steps up and judges someone else — Milich — will end up showing no morality whatsoever.

Eyes Wide Shut plays like a modern tale of human beings that haven’t changed that much since Schnitzler captured them 90 years ago. However, it’s not a cautionary tale, but a quiet acceptance of the ordinary in all its impossibilities. Stanley Kubrick has never been so humane, and probably this is why Eyes Wide Shut will always stand for how I want to remember the great director.

Links

- Elena Lazic on Eyes Wide Shut

- Jake Cole on Creed

- Ignatiy Vishnevetsky on Bridge of Spies

- Alberto Pezzotta on Salò